Architecture that Impacts Community & a Community that Impacts Architecture

Make it stand out

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Let me tell you all about this final sociology assignment that I enjoyed. We were asked to write a paper. Though I do not enjoy writing, for once, I was excited to come up with a project proposal that followed the guide of Karl Marx’s Class Conflict Theory. I knew from the beginning that it would be about architecture and power dynamics. By this point, I was entrenched in architecture theory, so to pair this with the study of social problems meant that I could take a unique look at architecture and urbanism. The topic of my paper was “The integration of White supremacy into urban planning and design.” By recalling my classes in urbanism and sociology for my project, I was able to uncover and better understand many of the social dynamics that affect my communities. The last portion of my abstract was about the power of actions performed on the urban scale. A single planning decision can affect not only the city but also the region around it. However, not every resident experiences the same gains or losses from these calls. In America particularly, the planning of urban cores has been under the influence of ideas that uphold a utopian White American society.

I came from the most diverse town in Massachusetts. Even though it was not perfect, I love my hometown, and I have so much pride and gratitude for it. Randolph was filled with many faces and cultures and a true sense of diversity that I have yet to find anywhere else. As a young Black Queer kid, it was important for me to explore the extent of my identity and try new things. I was active in my community. I played sports in my town’s recreational leagues. In middle school, I played in the orchestral and jazz bands. In high school, I was a member of the dance team, captain of the cheer squad, varsity hurdle captain, and part of the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) program that allowed me to “nerd out” over science. Along the way, I discovered my happiest place in art.

On the one hand, I would say that my interest in building blocks, drawing, and painting, paired with my affinity for dense and busy urban life, were seen as two separate things. However, it wasn’t until I had an art teacher that noticed my interest in drawing perspectives. She told me how perspectival drawings are used in architectural design communication. At that point, architecture was introduced to me as a possible occupation and one that would provide a comfortable livelihood. Before that moment, I hadn’t thought about architecture, nor had I known any architects in my community.

In my graduating high school class, only three students, including myself, showed interest in architecture as an occupation. Out of the three, two of us were Black. The other Black student was a friend of mine who couldn’t afford the cost of college and therefore did not attend. The moment she couldn’t afford school to study architecture was my first interaction with the complex topic of diversity in architecture.

As a young, first-generation, Black Queer male working towards becoming a future architect, I was overjoyed yet simultaneously worried about my circumstances. After my first trip to Wentworth [Institute of Technology], I realized that the jokes I heard in high school about being one of the “token” Black students were not far off from reality. There was a distinct moment when I realized that I was one of a few Black students at the new-student orientation. I felt disconnected and out of place. Not only was I a racial/ethnic minority, but I was a Queer one too.

Walking around orientation like a deer in headlights, I was visibly lost and alone. Finally, a bright and cheerful student came up and introduced himself to me. That was the start of an amazing camaraderie between Kai and me. Unbeknownst to me, he had identified me as a fellow Queer person. He wanted to connect as he was also searching for community. Unbeknownst to Kai, I was at an important pivotal moment in my life.

Kai allowed me to express myself in a way I hadn’t done before. It gave me a sense of community. I relied on him much like two members in the same house in the Ballroom Scene.* Kai became my study buddy, soundboard, and friend to hang out with and “kiki” with. He was great at networking, which taught this introvert how to come out of his shell. He also introduced me to other Queer students. It is important to mention that my dear friend Kai was a White Queer person; with that in mind, I was still looking to meet other Black and minority students. In walks Neil.

Neil was the NOMAS (National Organization of Minority Architecture Students) copresident. He introduced himself personally and invited me to my first NOMAS meeting. Let me explain why that was important to my collegiate experience. First off, he was a Queer Black male at a predominantly White institution—for that, I had to stan—but secondly, he also was about rallying together a community for support and progression.

It is very easy to call Neil my first mentor in architecture. We had very real conversations about life and experiences, fears and joys, and future ideas and past failures. He taught me a lot about how architecture has been inaccessible to Black and Brown people and introduced how larger city planning has intentionally created segregated cities. Finally, Neil encouraged me to run for NOMAS co-president to be his successor. He had seen some sort of potential in me that I have yet to discover in myself. From there, I filled out the ballot to run. Interestingly enough, together with my friend Kai, we served as co-presidents from 2018 to the end of 2021, when we graduated.

As one of my school’s NOMAS chapter co-presidents, I took the same approach when recruiting new members Neil had once done with me. I wanted to be the catalyst for creating a culture and community of people deeply concerned with the prosperity of the ones around them. This became an integral point of our planning and event coordination. We held many events with NOMAS that mainly focused on community building and had a firm foundation in professional development, knowledge dispersal, diversity equity, and inclusion.

Fast-forwarding for a bit. At the time of my commencement, only six other Black students graduated with me. Some reasons why the retention rate was not higher for the students of color were because (1) many of them felt a lack of community, belonging, and support, (2) they realized architecture was not for them or, (3) they could not afford the financial burden of college. I know several students who had professors tell them to quit architecture. Nonetheless, the remainder of the Black student population in my cohort became a close-knit group of friends. This micro-community of young Black architects in training who understood each other’s identities and experiences allowed us to become the braces for one another under serious compressive and tensile force. This translated later to our accountability for one another to produce responsive projects that did more than fulfill the duties of the brief but also responded to the socio-cultural aspects of the predominantly non-White communities our projects were based.

HOLC Redlinig Map of Study Area

The city of Boston is not absolved from inflicting the same

One topic we discussed in NOMAS a lot was “redlining”—the topic of a sociology paper—which is a part of planning and urban design history that deeply interests me. It is important to remember that America is a nation built for affluent White Anglo-Saxon Protestant citizens at the expense of Black, Indigenous, other non- White people, and poor White people. Many actions taken by the government just two generations ago, explicitly made dog-whistle policies to undermine the developments of Black and Brown communities to uphold White supremacist and capitalistic desires. The practice of “redlining” was a coded measure to ensure that Black and Brown families could not invest in housing stock and intermix with White communities. It had evolved from blatant anti-Black ordinances like Baltimore’s in 1910.

Though a variety of constitutional violations made overt segregationist policies illegal, there was a strong determination to enact racist policies, which was eventually done covertly through proxy variables. “Redlining” achieved this through a grading system that ranked districts into four categories: Most Desirable (green), Still Desirable (blue), Declining (yellow), and Hazardous (red). The metrics of the system took into account amenities like access to public parks, tree-lined streets, supply of housing stock, and demographic composition, amongst others. These zones were used to determine if appraisal values of homes would remain stable and assess the risk in lending loans to borrowers and their respective neighborhoods. Though the redlining system is rooted in home loan lending, eventually, U.S. Federal Government agencies, local governments, and private entities used the practice to deny services directly or indirectly by upping prices.

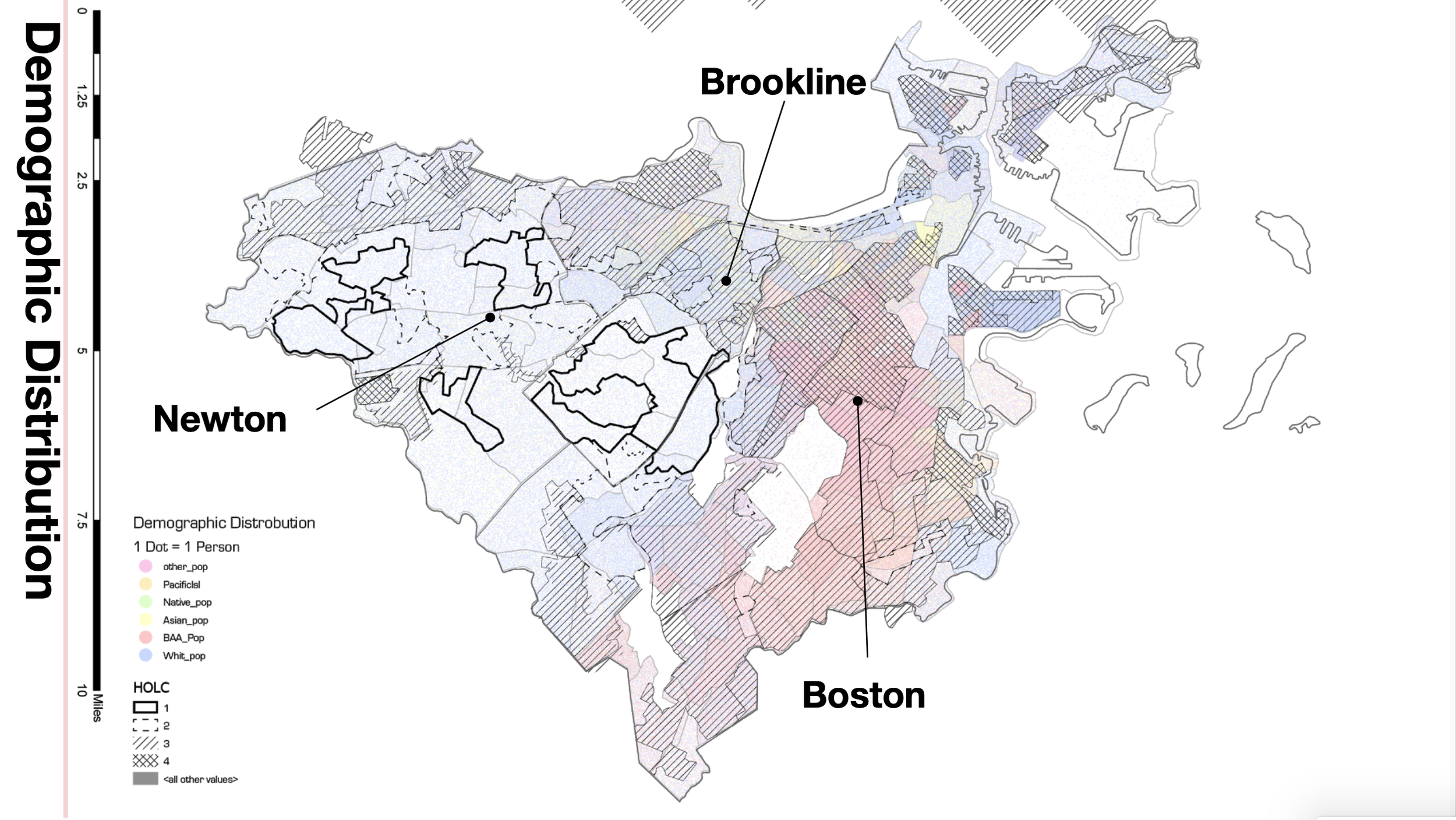

The dispersal of ethnic and racial groups across the study area aligns with the grading zones of the HOLC maps of Boston. Zones coded red—hatch pattern 4— and yellow—hatch pattern 3— contain the highest concentration of non-white citizens of the three cities. As noted, the areas zoned red/3 have experienced the highest levels of disinvestment and neglect by the city. The census data provided in the map is from 2018; it also highlights the segregation still seen in the city and the areas facing gentrification in the twenty-first century

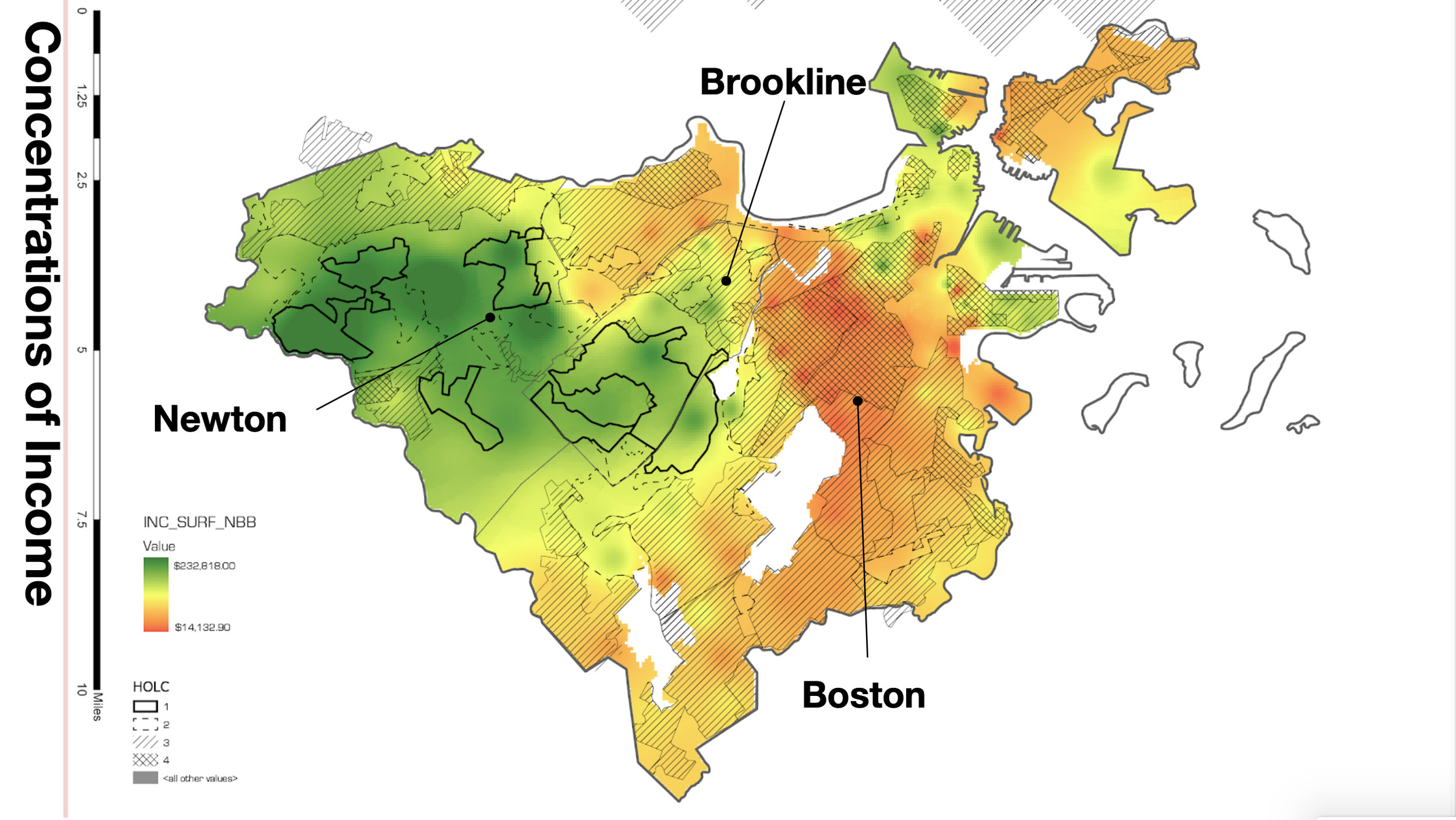

Due to the restrictions to wealth accumulation assets, the inability of black and other people of color to attain resources to better their lives, and the allocation of money to more “desirable” parts of the study area; the areas that are ranked red and yellow over generations still have a lower median income that areas that are predominantly white and ranked as a one or a two.

During the height of the pandemic, everyone was forced to see the world outside of the tint of their rose-colored glasses. Faced with the gross racial inequities displayed in the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, the rise in Asian American hate crimes, among other social issues, it forced America to engage in conversations and evaluate the ways White-supremacist-capitalism and the subsequent inequality plays a part in the spaces people occupy, including the field of architecture. Historically, planning has been used to segregate and oppress communities. Reimagining the design and planning profession begins with acknowledging the influence of architects on communities, architects as individuals, and the need for historical honesty and inclusion within the field.

I wish to work in design on an urban scale in the future. I love cities with all the complexity of infrastructure, socio-cultural aspects, and the potential future of urbanization. As a designer, I can affect the culture and daily lives of people in cities. I know that my experiences are impacted by architecture. Now with my architectural lens, I have a responsibility to be impactful within architecture for those in my communities. I see my life up to now being similar to Tupac’s “The Rose That Grew from Concrete’’ which has and will add to the ecosystem of the concrete jungle. I think that my physical and social environment has shaped my direction in the field. I want to be a designer with intention. I want to focus my work on embracing and celebrating all people. I want to allow Black, Queer, and firstgeneration to see themselves in me. I want them to feel included and dispel antiquated notions of social stability and racial hierarchy from the urban context.

I dedicate this essay to all who have been underrepresented and looked over. To the Black designers whose names are unknown, the architects of pre-colonial Africa, and most importantly, those who have helped me reach this point in my life.